At least 15 people have died in the Democratic Republic of Congo following a new outbreak of the Ebola virus, the Ministry of Health confirmed on Friday, raising fresh concerns about the country’s ability to contain one of the world’s deadliest diseases. Officials said the outbreak began when a 34-year-old pregnant woman in central Kasai province was admitted to hospital last month with a high fever and persistent vomiting. She died within hours from multiple organ failure, and laboratory tests later confirmed she had contracted the Zaire strain of Ebola.

Since the first case, authorities have recorded 28 suspected infections, including four health workers who became ill while treating patients. The virus is feared to be spreading within communities as local hospitals struggle to isolate new cases. The World Health Organization said in a statement that the risk of further transmission is high, warning that “case numbers are likely to increase as transmission is ongoing.” Emergency response teams have already been dispatched to the area.

The outbreak is the sixteenth in DR Congo since Ebola was first identified in the country in 1976. Previous crises have left deep scars, particularly the 2018 to 2020 epidemic in the east that killed more than 2,000 people. Though smaller in scale, the last outbreak three years ago still claimed six lives and exposed the vulnerabilities of the country’s health infrastructure.

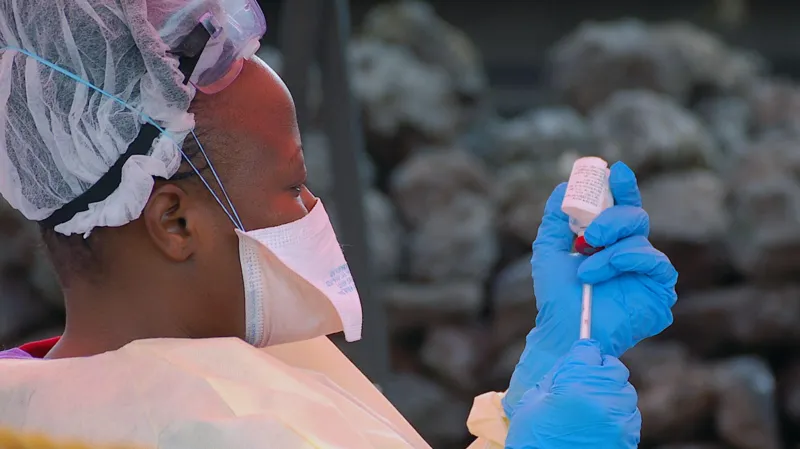

To contain the spread, Congolese health authorities confirmed they are deploying a stockpile of 2,000 doses of the Ervebo vaccine, which has been shown to provide protection against the Zaire strain. Vaccination teams are expected to focus first on health workers and those in close contact with confirmed cases, as part of a “ring vaccination” strategy. The government has urged residents to follow strict safety guidelines, including frequent handwashing, limiting physical contact, and avoiding large gatherings in affected areas.

Despite these measures, health experts warn that ongoing insecurity, weak infrastructure, and mistrust of government institutions could complicate the response. Many communities in remote parts of the Kasai region remain hard to reach, and doctors fear that unreported cases may already exist in villages where access is limited. Humanitarian organizations are also struggling to deliver medical supplies because of poor roads and sporadic violence.

The Ebola virus spreads through direct contact with the bodily fluids of an infected person, including blood, vomit, and feces. Its incubation period can last from two to 21 days, making it difficult to detect in the early stages. Although survival rates have improved with new treatments and vaccines, fatality rates still range from 25 to 90 percent depending on the strain and timeliness of care.

Local residents say fear is rising as word spreads of the outbreak. Some families have begun fleeing to nearby towns in hopes of avoiding infection, while others are reluctant to bring sick relatives to hospitals, fearing both the disease and the stigma that accompanies it. Religious and community leaders are being called upon to support public health campaigns aimed at reducing misinformation and encouraging cooperation with medical workers.

For now, the government and its international partners are racing to contain the outbreak before it escalates. Whether the current effort will succeed depends on how quickly new cases can be identified, isolated, and treated. Officials say the coming weeks will be decisive, as the virus has already proven how devastating it can be when outbreaks are not controlled at the earliest stage.